The conventional wisdom of how antioxidants such as vitamin C help prevent cancer growth is that they grab up volatile oxygen free radical molecules and prevent the damage they are known to do to our delicate DNA. The Hopkins study, led by Chi Dang, M.D., Ph.D., professor of medicine and oncology and Johns Hopkins Family Professor in Oncology Research, unexpectedly found that the antioxidants’ actual role may be to destabilize a tumor’s ability to grow under oxygen-starved conditions. Their work is detailed in “Cancer Cell” journal. http://www.johnshopkinshealthalerts.com/reports/healthy_living/1548-1.html

What is ascorbic acid?

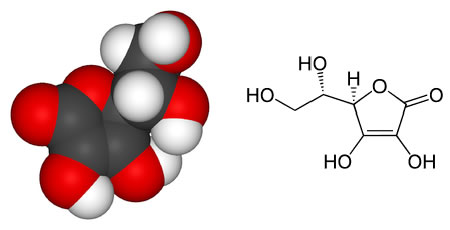

Ascorbic acid is a naturally occurring organic compound with antioxidant properties. It is a white solid, but impure samples can appear yellowish. It dissolves well in water to give mildly acidic solutions. Ascorbic acid is one form (“vitamer”) of vitamin C. The name is derived from a- (meaning “no”) and scorbutus (scurvy), the disease caused by a deficiency of vitamin C. In living organisms ascorbate acts as an antioxidant by protecting the body against oxidative stress. It is also a cofactor in at least eight enzymatic reactions including several collagen synthesis reactions that, when dysfunctional, cause the most severe symptoms of scurvy.

Model of a vitamin C molecule. Black is carbon, red is oxygen, and white is hydrogen

Natural and synthetic L-ascorbic acid are chemically identical, and there are no known differences in their biological activity

Biosynthesis

Ascorbic acid is found in plants, animals, and single-cell organisms where it is produced from glucose. All animals either make it, eat it, or else die from scurvy due to lack of it. Reptiles and older orders of birds make ascorbic acid in their kidneys. Recent orders of birds and most mammals make ascorbic acid in their liver where the enzyme L-gulonolactone oxidase is required to convert glucose to ascorbic acid. Primates, including humans, and guinea pigs do not synthesize vitamin C internally. Nearly all other animals synthesize vitamin C internally, maintaining cellular vitamin C concentrations that are considerably higher than those achieved with the Recommended Daily Intake set for humans. Four enzymes are required to turn glucose into ascorbic acid. We humans have the first three enzymes in our livers that are required for ascorbic acid synthesis. We are missing the fourth enzyme, L-gulonolactone oxidase. This missing enzyme is what blocks the liver production of vitamin C in humans. Animals that are not missing L-gulonolactone oxidase make and release considerable amounts of ascorbic acid into the bloodstream on a continuous basis.

Most animal species make in the neighborhood of 5,000-10,000 mg/day of vitamin C in their own bodies; this is the norm for all mammals except primates, some fruit eating bats, and guinea pigs. And it is known that during times of stress or illness, the majority of animal species dramatically increase their need and production of vitamin C. We humans can respond to this increased need by taking mega-doses of vitamin C when we start to feel a virus taking hold. When we do so, our bodies will be able to fight it off more readily.

The reason we are missing the fourth enzyme is because of a genetic mutation that occurred many millions of years ago to our early primate ancestors.

The Bioavailability of Different Forms of Vitamin C (Ascorbic Acid)

Jane Higdon, R.N., Ph.D.

LPI Research Associate Linus Pauling Institute:

In the rapidly expanding market of dietary supplements, it is possible to find vitamin C in many different forms with many claims regarding its efficacy or bioavailability. Bioavailability refers to the degree to which a nutrient (or drug) becomes available to the target tissue after it has been administered. We reviewed the literature for the results of scientific research on the bioavailability of different forms of vitamin C.

Natural vs. synthetic ascorbic acid

Natural and synthetic L-ascorbic acid are chemically identical, and there are no known differences in their biological activity. The possibility that the bioavailability of L-ascorbic acid from natural sources might differ from that of synthetic ascorbic acid was investigated in at least two human studies, and no clinically significant differences were observed. A study of 12 males (six smokers and six nonsmokers) found the bioavailability of synthetic ascorbic acid (powder administered in water) to be slightly superior to that of orange juice, based on blood levels of ascorbic acid, and not different based on ascorbic acid in leukocytes (white blood cells). A study in 68 male nonsmokers found that ascorbic acid consumed in cooked broccoli, orange juice, orange slices, and as synthetic ascorbic acid tablets are equally bioavailable, as measured by plasma ascorbic acid levels.

Different forms of ascorbic acid (powders, tablets, etc.)

The gastrointestinal absorption of ascorbic acid occurs through an active transport process, as well as through passive diffusion. At low gastrointestinal concentrations of ascorbic acid active transport predominates, while at high gastrointestinal concentrations active transport becomes saturated, leaving only passive diffusion. In theory, slowing down the rate of stomach emptying (e.g., by taking ascorbic acid with food or taking a slow-release form of ascorbic acid) should increase its absorption. While the bioavailability of ascorbic acid appears equivalent whether it is in the form of powder, chewable tablets, or non-chewable tablets, the bioavailability of ascorbic acid from slow-release preparations is less certain.

A study of three men and one woman found 1 gram of ascorbic acid to be equally well absorbed from solution, tablets, and chewable tablets, but the absorption from a timed-release capsule was 50% lower. Absorption was assessed by measuring urinary excretion of ascorbic acid after an intravenous dose of ascorbic acid and then comparing it to urinary excretions after the oral dosage forms. A more recent study examined the plasma levels of ascorbic acid in 59 male smokers supplemented for two months with either 500 mg/day of slow-release ascorbic acid, 500 mg/day of plain ascorbic acid, or a placebo. After two months of supplementation no significant differences in plasma ascorbic acid levels between the slow-release and plain ascorbic acid groups were found.

Mineral ascorbates

Mineral salts of ascorbic acid (mineral ascorbates) are buffered, and therefore, less acidic. Thus, mineral ascorbates are often recommended to people who experience gastrointestinal problems (upset stomach or diarrhea) with plain ascorbic acid. There appears to be little scientific research to support or refute the claim that mineral ascorbates are less irritating to the gastrointestinal tract. When mineral salts of ascorbic acid are taken, both the ascorbic acid and the mineral appear to be well absorbed, so it is important to take consider the dose of the mineral accompanying the ascorbic acid when taking large doses of mineral ascorbates. For the following discussion, it should be noted that 1 gram (g)= 1,000 milligrams (mg) and 1 milligram (mg) = 1,000 micrograms (mcg). Mineral ascorbates are available in the following forms:

- Sodium ascorbate: 1,000 mg of sodium ascorbate generally contains 111 mg of sodium. Individuals following low-sodium diets (e.g., for high blood pressure) are generally advised to keep their total dietary sodium intake to less than 2,500 mg/day. Thus, megadoses of vitamin C in the form of sodium ascorbate could significantly increase sodium intake (see Sodium Chloride).

- Calcium ascorbate: Calcium ascorbate generally provides 90-110 mg of calcium (890-910 mg of ascorbic acid) per 1,000 mg of calcium ascorbate. Calcium in this form appears to be reasonably well absorbed. The recommended dietary calcium intake for adults is 1,000 to 1,200 mg/day. Total calcium intake should not exceed the UL, which is 2,500 mg/day for adults aged 19-50 years and 2,000 mg/day for adults older than 50 years (see Calcium). Calcium ascorbate can be purchased as a powder and readily dissolves in water or juice. In this buffered form ascorbate is completely safe for the mouth and sensitive stomach and can be applied directly to the gums to help heal infections [8]. It is a little more expensive than the equivalent ascorbic acid and bicarbonate but more convenient. Calcium ascorbate has the advantage of being non-acidic. It has a slightly metallic taste and is astringent but not sour like ascorbic acid. 1000 mg of calcium ascorbate contains about 110 mg of calcium.

The following mineral ascorbates are more likely to be found in combination with other mineral ascorbates, as well as other minerals. It’s a good idea to check the labels of dietary supplements for the ascorbic acid dose as well as the dose of each mineral. Recommended dietary intakes and maximum upper levels of intake (when available) are listed after the individual mineral ascorbates below:

- Potassium ascorbate: The minimal requirement for potassium is thought to be between 1.6 and 2.0 g/day. Fruits and vegetables are rich sources of potassium, and a diet rich in fruits and vegetables may provide as much as 8 to 11 g/day. Acute and potentially fatal potassium toxicity (hyperkalemia) is thought to occur at a daily intake of about 18 g/day of potassium in adults. Individuals taking potassium-sparing diuretics and those with renal insufficiency (kidney failure) should avoid significant intake of potassium ascorbate. The purest form of commercially available potassium ascorbate contains 0.175 grams (175 mg) of potassium per gram of ascorbate (see Potassium).

- Magnesium ascorbate: The recommended dietary allowance (RDA) for magnesium is 400-420 mg/day for adult men and 310-320 mg/day for adult women. The upper level (UL) of intake for magnesium from supplements should not exceed 350 mg/day (see Magnesium).

- Zinc ascorbate: The RDA for zinc is 11 mg/day for adult men and 8 mg/day for adult women. The upper level (UL) of zinc intake for adults should not exceed 40 mg/day (see Zinc).

- Molybdenum ascorbate: The RDA for molybdenum is 45 micrograms (mcg)/day for adult men and women. The upper level (UL) of molybdenum intake for adults should not exceed 2,000 mcg (2 mg)/day (see Molybdenum).

- Chromium ascorbate: The recommended dietary intake (AI) for chromium is 30-35 mcg/day for adult men and 20-25 mcg/day for adult women. A maximum upper level (UL) of intake has not been determined by the U.S. Food and Nutrition Board (see Chromium).

- Manganese ascorbate: The recommended dietary intake (AI) for manganese is 2.3 mg/day for adult men and 1.8 mg/day for adult women. The upper level (UL) of intake for manganese for adults should not exceed 11 mg/day. Manganese ascorbate is found in some preparations of glucosamine and chondroitin sulfate, and following the recommended dose on the label of such supplements could result in a daily intake exceeding the upper level for manganese (see Manganese).

Other formulations of vitamin C.

Another formulation of vitamin C, liposomal-encapsulated vitamin C (e.g., Lypo-spheric™ vitamin C) is now commercially available. As you probably know, vitamin C is water soluble. But cell walls are made of fats, thus making C difficult to penetrate even if the blood is saturated. The new oral method is known as liposomal encapsulated vitamin C. It mixes ascorbic acid powder with lecithin on a nanoparticle level. The result is a gummy mixture of C “encapsulated” in fats.

Vitamin C megadose –Miracle

Vitamin C is found in high concentrations in immune cells, and is consumed quickly during infections. It is not certain how vitamin C interacts with the immune system; it has been hypothesized to modulate the activities of phagocytes, the production of cytokines and lymphocytes, and the number of cell adhesion molecules in monocytes.

The first physician to aggressively use vitamin C to cure diseases was Frederick R. Klenner, M.D. beginning back in the early 1940’s. Klenner’s main subspecialty was diseases of the chest, but he became interested in the use of very large doses of Vitamin C in the treatment of a wide range of illness. Many of his experiments were performed on himself. In 1948, he published his first paper on the use of large doses of Vitamin C in the treatment of virus diseases.

In 1949 Klenner published in and presented a paper to the American Medical Association detailing the complete cure of 60 out of 60 of his patients with polio using intravenous sodium ascorbate injection Galloway and Seifert cited Klenner’s presentation to the AMA in a paper of theirs. Generally, he gave 350 to 700 mg per kilogram body weight per day.

This seems like an impossible list of vitamin C cures. At this point, you can either dismiss the subject or investigate further. Dr. Klenner chose to investigate. The result? He used massive doses of vitamin C for over forty years of family practice. He wrote dozens of medical papers on the subject. A complete list of them is in the Clinical Guide to the Use of Vitamin C, edited by Lendon H. Smith, M.D., Life Sciences Press, Tacoma, WA (1988).

It is difficult to ignore his success, but it has been done. Dr. Klenner wrote: “Some physicians would stand by and see their patient die rather than use ascorbic acid (Vitamin C) because in their finite minds it exists only as a vitamin.”

1. For over three decades investigators have researched the use of ascorbic acid to treat cancer.

2. The investigation of vitamin C as a treatment for cancer was pioneered by Klenner, Cameron,Pauling, Campbell, Hoffer, and Riordan (see references).

3. Both oral ascorbic acid (hence forth called vitamin C) and intravenous ascorbate (IVC) have been used to treat cancers in primary (known residual tumor) and adjuvant (after tumor removal) settings.

4. Oral vitamin C supplementation (and other antioxidants) has been used to help prevent cancer onset and its recurrence.

5. Standard chemotherapy and radiation protocols have used adjuvant IVC to augment their effectiveness and decrease their side effects.

6. Primary IVC therapy with or without other nutritional supplementation has shown success in decreasing symptoms, improving quality of life, and prolonging survival in cancer patients.

How much vitamin C is an effective therapeutic dose?

Dr. Klenner gave up to 300,000 milligrams (mg) per day. Generally, he gave 350 to 700 mg per kilogram body weight per day. That is a lot of Vitamin C.

But then again, look at that list of successes.

Dr. Klenner emphasized that small amounts do not work. He said, “If you want results, use adequate ascorbic acid (Vitamin C).”

Oral vitamin C does not produce a blood level high enough to kill cancer cells. From studies of Riordan clinic, they concluded that tumor cells become susceptible to high-dose vitamin C at plasma levels of 350 to 400 mg/dL, where redox cycling creates cellular peroxidation. This pro-oxidant effect of IVC induces apoptosis in catalase-deficient cancer cells while sparing non-cancerous cells from oxidative damage. The Riordan Clinic has pioneered IVC therapy over 30 years

- At 350 to 400 mg/dL, vitamin C is delivered as a pro-drug to the extracellular space where it interacts with metal ions in a Fenton reaction, generating significant interstitial H2O2.Normal cells are not affected while cancer cells, due to the catalase deficiency, are destroyed. Due to increased glucose receptors on the cancer cell membranes, vitamin C may accumulate up to five times the concentration than in normal cells

- Vitamin C promotes healthy mitochondria function, stimulates the immune system to produce interferon, to increase NK cell numbers, phagocytosis with enhanced migration and killing function. Vitamin C reduces oxidative damage to the p53 (apoptosis-regulating) gene due to chemo and radiation. This helps to prevent the DNA damage and mutation that would otherwise render cancer cell apoptosis and death nonfunctional.

- Vitamin C helps in the production of collagen and carnitine for fibrous tissue formation that helps to “wall off” the tumor. It also helps in the formation of connective tissue, cartilage, bone matrix, tooth dentin, skin, and tendons.

- Vitamin C helps in the conversion of amino acids to neurotransmitters; decreases the production of prostaglandin E2 and, therefore, the inflammatory response; and enhances stem cell production for normal tissue healing.

For maximum understanding you may access Dr Riordan’s treatment protocol, available at the following link www.riordanclinic.org/education/symposium/s2010/

YOU CAN READ BOTH THE CLINICAL GUIDE and THE HEALING FACTOR FOR FREE

Many readers have long been hunting for copies of these amazingly valuable books. Your wishes have been answered. Dr. Klenner’s Clinical Guide to the Use of Vitamin C is now posted in its entirety at http://www.seanet.com/~alexs/ascorbate/198x/smith-lh-clinical_guide_1988.htm

The complete text of Irwin Stone’s book The Healing Factor is now posted for free reading at http://vitamincfoundation.org/stone/

In 1969, Dean Burk, Ph.D., U.S. National Cancer Institute and his group at the National Cancer Institute published in Oncology a paper describing their findings that ascorbate would kill cancer cells and was harmless to normal cells (Benade, 1969). The opening sentence reads, “The present study shows that ascorbate (vitamin C) is highly toxic or lethal to Ehrlich ascites carcinoma cells in vitro.” They wrote further, “The great advantage that ascorbates . . . possess as potential anticancer agents is that they are, like penicillin, remarkably nontoxic to normal body tissues, and they may be administered to animals in extremely large doses (up to 5 or more gm/kg) without notable harmful pharmacological effects.” Let me remind you that 5 g of ascorbate per kilogram of body weight, for a 150-pound adult, amounts to 350 g or 350,000 mg, over three-quarters of a pound.

They further state, “In our view, the future of effective cancer chemotherapy will not rest on the use of host-toxic compounds now so widely employed, but upon virtually host-nontoxic compounds that are lethal to cancer cells of which ascorbate . . . represents an excellent prototype.” They also point out that ascorbate was never tested for its anticancer effects by the Cancer Chemotherapy National Service Center, because it was too nontoxic to fit into their screening program.

This very high concentration of vitamin C is critical in terms of achieving a chemotherapeutic, cytotoxic – tumour cell destruction – effect. If it is feasible to have a Hickman line put in the patient, extraordinary doses of vitamin C – anything between 50g to 100g, depending on the malignancy of the cancer, – can be self-administered at home on a daily to weekly basis over a period of months, stepping down or up in frequency according to the individual response.

Acid Balance in the Body

Does taking large quantities of an acid, even a weak acid like ascorbate, tip the body’s acid balance (pH) causing health problems? No, because the body actively and constantly controls the pH of the bloodstream. The kidneys regulate the acid in the body over a long time period, hours to days, by selectively excreting either acid or basic components in urine. Over a shorter time period, minutes to hours, if the blood is too acid, the autonomic nervous system increases the rate of breathing, thereby removing more carbon dioxide from the blood, reducing its acidity. Some foods can indirectly cause acidity. For example, when more protein is eaten than necessary for maintenance and growth, it is metabolized into acid, which must be removed by the kidneys, generally as uric acid. In this case, calcium and/or magnesium are excreted along with the acid in the urine which can deplete our supplies of calcium and magnesium. However, because ascorbic acid is a weak acid, we can tolerate a lot before it will much affect the body’s acidity. Although there have been allegations about vitamin C supposedly causing kidney stones, there is no evidence for this, and its acidity and diuretic tendency actually tends to reduce kidney stones in most people who are prone to them. Ascorbic acid dissolves calcium phosphate stones and dissolves struvite stones. Additionally, while vitamin C does increase oxalate excretion, vitamin C simultaneously inhibits the union of calcium and oxalate.

Possible adverse effects

While being harmless in most typical quantities, as with all substances to which the human body is exposed, vitamin C can still cause harm under certain conditions. In the medical community, these are known as contraindications.

- As vitamin C enhances iron absorption for iron deficiency, iron overload may become an issue to people with rare iron-overload conditions, such as Beta (β) thalassemias and hemochromatosis.[citation needed]

- A genetic condition that results in inadequate levels of the enzyme glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PD) can cause sufferers to develop hemolytic anemia after ingesting specific oxidizing substances (favism), such as very large dosages of vitamin C. Common, inexpensive tests exist to determine G6PD deficiency.[citation needed]

- There is a longstanding belief among the mainstream medical community that vitamin C causes kidney stones, which seems based little on science. Although some individual recent studies have found a relationship, there is no clear relationship between excess ascorbic acid intake and kidney stone formation.

- Hemolysis has been reported in patients with G6PD deficiency when given high-dose IVC. The G6PD level should be assessed before beginning IVC

Purpose of this published study is scientific information and education, it should not be used for diagnosing or treating a health problem or disease. This website is designed for general education and information purposes only and does not substitute for professional medical advice, examination, diagnosis or treatment.

References

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Vitamin_C_megadosage

http://orthomolecular.org/resources/omns/v05n10.shtml

“Vitamin and mineral requirements in human nutrition, 2nd edition” (PDF). World Health Organization. 2004. Retrieved 2007-02-20.

Gropper SS, Smith JL, Grodd JL (2004). Advanced Nutrition and Human Metabolism (4th ed.). Belmont, CA. USA: Thomson Wadsworth. pp. 260–275.

http://www.naturalnews.com/034646_vitamin_C_encapsulated_mega_dose.html

http://lpi.oregonstate.edu/infocenter/vitamins/vitaminC/vitCform.html

Yeom CH, Jung GC, Song KJ (2007). “Changes of terminal cancer patients’ health-related quality of life after high dose vitamin C administration”. J. Korean Med. Sci. 22 (1): 7–11. DOI:10.3346/jkms.2007.22.1.7. PMC 2693571. PMID 17297243. Retrieved 2007-08-03.

“Vitamin C (Ascorbic Acid)”. University of Maryland Medical Center. April 2002. Retrieved 2007-02-19.

Pauling L (1970). “Evolution and the need for ascorbic acid”. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 67 (4): 1643–1648. DOI:10.1073/pnas.67.4.1643. PMC 283405. PMID 5275366. Retrieved 2007-07-27.

Stone, I. (1979). “Homo sapiens ascorbicus, a biochemically corrected robust human mutant”. Medical hypotheses 5 (6): 711–721. DOI:10.1016/0306-9877(79)90093-8. PMID 491997. edit

Douglas RM, Hemilä H (2005). “Vitamin C for Preventing and Treating the Common Cold”. PLoS Medicine 2 (6): e168. DOI:10.1371/journal.pmed.0020168. PMC 1160577. PMID 15971944.

Gorton, HC,; Jarvis K. (1999 Oct;22). “The effectiveness of vitamin C in preventing and relieving the symptoms of virus-induced respiratory infections.”. Journal of Manipulative and Physiological Therapeutics (PubMed) 8: 530–533.

Hemilä, H; Chalker E, Douglas B (2000). “Vitamin C for preventing and treating the common cold”. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 3 (2): CD000980. DOI:10.1002/14651858.CD000980. ISSN 1464-780X. PMID 10796569.

Houston, M. C. (2010). “The role of cellular micronutrient analysis, nutraceuticals, vitamins, antioxidants and minerals in the prevention and treatment of hypertension and cardiovascular disease”. Therapeutic Advances in Cardiovascular Disease 4 (3): 165. DOI:10.1177/1753944710368205. PMID 20400494. edit

Cameron E, Pauling L (October 1976). “Supplemental ascorbate in the supportive treatment of cancer: Prolongation of survival times in terminal human cancer”. PNAS 73 (10): 3685–3689. Bibcode 1976PNAS…73.3685C. DOI:10.1073/pnas.73.10.3685. PMC 431183. PMID 1068480.

Creagan ET, Moertel CG, O’Fallon JR, et al. (September 1979). “Failure of high-dose vitamin C (ascorbic acid) therapy to benefit patients with advanced cancer. A controlled trial”. NEJM 301 (13): 687–690. DOI:10.1056/NEJM197909273011303. PMID 384241.

Moertel CG, Fleming TR, Creagan ET, Rubin J, O’Connell MJ, Ames MM (January 1985). “High-dose vitamin C versus placebo in the treatment of patients with advanced cancer who have had no prior chemotherapy. A randomized double-blind comparison”. NEJM 312 (3): 137–141. DOI:10.1056/NEJM198501173120301. PMID 3880867.

Tschetter, L; et al. (1983). “A community-based study of vitamin C (ascorbic acid) in patients with advanced cancer”. Proceedings of the American Society of Clinical Oncology 2: 92.

DeWys, WD (1982). “How to evaluate a new treatment for cancer”. Your Patient and Cancer 2 (5): 31–36.

Barrett, S (2008-10-23). “High Doses of Vitamin C Are Not Effective as a Cancer Treatment”. Quackwatch. Retrieved 2010-05-06.

Riordan HD, Casciari JJ, González MJ, et al. (December 2005). “A pilot clinical study of continuous intravenous ascorbate in terminal cancer patients”. P R Health Sci J 24 (4): 269–276. PMID 16570523.

Hoffer LJ, Levine M, Assouline S, et al. (June 2008). “Phase I clinical trial of i.v. ascorbic acid in advanced malignancy”. Ann. Oncol. 19 (11): 1969. DOI:10.1093/annonc/mdn377. PMID 18544557.

Heaney ML, Gardner JR, Karasavvas N, et al. (October 2008). “Vitamin C antagonizes the cytotoxic effects of antineoplastic drugs”. Cancer Res. 68 (19): 8031–8038. DOI:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-1490. PMID 18829561.

Block, K; Koch, A; Mead, M; Tothy, P; Newman, R; Gyllenhaal, C (2007). “Impact of antioxidant supplementation on chemotherapeutic efficacy: A systematic review of the evidence from randomized controlled trials” (pdf). Cancer Treatment Reviews 33 (5): 407–418. DOI:10.1016/j.ctrv.2007.01.005. PMID 17367938. edit

Cabanillas, F (2010). “Vitamin C and cancer: what can we conclude–1,609 patients and 33 years later?”. Puerto Rico health sciences journal 29 (3): 215–7. PMID 20799507. edit

Giannini AJ, Loiselle RH, DiMarzio LR, Giannini MC (September 1987). “Augmentation of haloperidol by ascorbic acid in phencyclidine intoxication”. The American Journal of Psychiatry 144 (9): 1207–1209. PMID 3631319.

Choi, MD, DrPH, Hyon K.; Xiang Gao, MD, PhD; Gary Curhan, MD, ScD (March 9, 2009). “Vitamin C Intake and the Risk of Gout in Men”. Archives of Internal Medicine. 169 (5): 502–507. DOI:10.1001/archinternmed.2008.606. PMC 2767211. PMID 19273781.

Berger MM (October 2006). “Antioxidant micronutrients in major trauma and burns: evidence and practice”. Nutr Clin Pract 21 (5): 438–49. PMID 16998143.

Greenhalgh DG (2007). “Burn resuscitation”. J Burn Care Res 28 (4): 555–65. PMID 17665515.

Pham TN, Cancio LC, Gibran NS (2008). “American Burn Association practice guidelines burn shock resuscitation”. J Burn Care Res 29 (1): 257–66. DOI:10.1097/BCR.0b013e31815f3876. PMID 18182930.

Smith DC (March 1990). “‘Cured’ myasthenia”. Anaesthesia 45 (3): 252. PMID 1970713.

Goodwin JS, Tangum MR (November 1998). “Battling quackery: attitudes about micronutrient supplements in American academic medicine”. Arch. Intern. Med. 158 (20): 2187–2191. DOI:10.1001/archinte.158.20.2187. PMID 9818798.

Massey LK, Liebman M, Kynast-Gales SA (2005). “Ascorbate increases human oxaluria and kidney stone risk” (PDF). J. Nutr. 135 (7): 1673–1677. PMID 15987848.

Naidu KA (2003). “Vitamin C in human health and disease is still a mystery? An overview.” (PDF). J. Nutr. 2 (7): 7. DOI:10.1186/1475-2891-2-7. PMC 201008. PMID 14498993.

Dietary reference intakes for vitamin C, vitamin E, selenium, and carotenoids: a report of the Panel on Dietary Antioxidants and Related Compounds, Subcommittees on Upper Reference Levels of Nutrients and of Interpretation and Use of Dietary Reference Intakes, and the Standing Committee on the Scientific Evaluation of Dietary Reference Intakes, Food and Nutrition Board, Institute of Medicine. Washington, D.C: National Academy Press. 2000. pp. 156–161. ISBN 0-309-06949-1.

Nankivell, BJ; Murali KM (2008). “Renal failure from vitamin C after transplantation”. NEJM 358 (4): e4. DOI:10.1056/NEJMicm070984. PMID 18216350.

“Safety (MSDS) data for ascorbic acid”. Oxford University. October 9, 2005. Retrieved 2007-02-21.

E. B. Henry, A. Carswell, A. Wirz, V. Fyffe & K. E. L. Mccoll (September 2005). “Proton pump inhibitors reduce the bioavailability of dietary vitamin C”. Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics. Retrieved 2007-02-21.

C. Mowat, A. Carswell, A. Wirz, K.E. McColl (April 1999). “Omeprazole and dietary nitrate independently affect levels of vitamin C and nitrite in gastric juice.”. Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics. Retrieved 2011-02-14.

Loh HS, Watters K & Wilson CW (1 November 1973). “The Effects of Aspirin on the Metabolic Availability of Ascorbic Acid in Human Beings”. J Clin Pharmacol 13 (11): 480–486. PMID 4490672.

Basu TK (1982). “Vitamin C-aspirin interactions”. Int J Vitam Nutr Res Suppl 23: 83–90. PMID 6811490.

Ioannides C, Stone AN, Breacker PJ & Basu TK (1982). “Impairment of absorption of ascorbic acid following ingestion of aspirin in guinea pigs”. Biochem Pharmacol 31 (24): 4035–4038. DOI:10.1016/0006-2952(82)90652-9. PMID 6818974.

Vitamin C produces gene-damaging compounds Accessed July 2007

Balz Frei, Ph.D. (November, 2001). “Vitamin C Doesn’t Cause Cancer!”. Oregon State University. Retrieved 2007-02-21.

Perez-Cruz I, Cárcamo JM, Golde DW (January 2007). “Caspase-8 dependent TRAIL-induced apoptosis in cancer cell lines is inhibited by vitamin C and catalase”. Apoptosis 12 (1): 225–234. DOI:10.1007/s10495-006-0475-0. PMID 17031493.

Ian D. Podmore, Helen R. Griffiths, Karl E. Herbert, Nalini Mistry, Pratibha Mistry and Joseph Lunec (9 April 1998). “Vitamin C exhibits pro-oxidant properties”. Nature 392 (6676): 559. Bibcode 1998Natur.392..559P. DOI:10.1038/33308. PMID 9560150.

Hagfors, L; Leanderson P, Skoldstam L (2003). “Antioxidant intake, plasma antioxidants an oxidative stress in a randomized, controlled, parallel, maditerranean dietary intervention study on patients with rheumatoid arthritis.”. Nutr J: 30:2:5.

Hokama S, Toma C, Jahana M, et al. (2000). “Ascorbate conversion to oxalate in alkaline milieu and Proteus mirabilis culture”. Mol Urol 4 (4): 321–328. PMID 11156698.

Stephen Lawson (November 1999). “What About Vitamin C and Kidney Stones?”. The Linus Pauling Institute. Retrieved 2007-02-21.

Jacob RA, Skala JH, Omaye ST, Turnlund JR. (December 1987). “Effect of varying ascorbic acid intakes on copper absorption and ceruloplasmin levels of young men.”. J Nutr. 117 (12): 2109–2115. PMID 3694287.

Finley EB, Cerklewski FL (April 1983). “Influence of ascorbic acid supplementation on copper status in young adult men”. Am J Clin Nutr. 37 (4): 553–556. PMID 6837490.

Rautiainen S, Lindblad BE, Morgenstern R, Wolk A (February 2010). “Vitamin C supplements and the risk of age-related cataract: a population-based prospective cohort study in women”. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 91 (2): 487–493. DOI:10.3945/ajcn.2009.28528. PMID 19923367.

Harri Hemilä (January 2006). “Do vitamins C and E affect respiratory infections?” (PDF). University of Helsinki. Retrieved 2007-02-21.

Rath M, Pauling L (1990). “Immunological evidence for the accumulation of lipoprotein(a) in the atherosclerotic lesion of the hypoascorbemic guinea pig”. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 87 (23): 9388–9390. DOI:10.1073/pnas.87.23.9388. PMC 55170. PMID 2147514.

Rath M, Pauling L (1990). “Hypothesis: lipoprotein(a) is a surrogate for ascorbate”. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 87 (16): 6204–6207. DOI:10.1073/pnas.87.16.6204. PMC 54501. PMID 2143582.

Rath M, Pauling L (1992). “A unified theory of human cardiovascular disease leading the way to the abolition of this disease as a cause for human mortality”. Journal of Orthomolecular Medicine 7 (1): 5–15.

Nishikimi M, Kawai T, Yagi K (25 October 1992). “Guinea pigs possess a highly mutated gene for L-gulono-gamma-lactone oxidase, the key enzyme for L-ascorbic acid biosynthesis missing in this species”. J Biol Chem 267 (30): 21967–21972. PMID 1400507.

Ohta Y, Nishikimi M (October 1999). “Random nucleotide substitutions in primate nonfunctional gene for L-gulono-gamma-lactone oxidase, the missing enzyme in L-ascorbic acid biosynthesis”. Biochim Biophys Acta 1472 (1-2): 408–411. DOI:10.1016/S0304-4165(99)00123-3. PMID 10572964.

A trace of GLO was detected in only 1 of 34 bat species tested, across the range of 6 families of bats tested: See Jenness R, Birney E, Ayaz K (1980). “Variation of L-gulonolactone oxidase activity in placental mammals”. Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology 67B: 195–204. Earlier reports of only fruit bats being deficient were based on smaller samples.

Carlos Martinez del Rio (July 1997). “Can passerines synthesize vitamin C?”. The Auk.

Pollock JI, Mullin RJ (May 1987). “Vitamin C biosynthesis in prosimians: evidence for the anthropoid affinity of Tarsius”. Am J Phys Anthropol 73 (1): 65–70. DOI:10.1002/ajpa.1330730106. PMID 3113259.

Stone, Irwin (1972). The Healing Factor: Vitamin C Against Disease. Grosset and Dunlap. ISBN 0-448-11693-6. OCLC 3967737.

Pauling, Linus (1970). “Evolution and the need for ascorbic acid”. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 67 (4): 1643–1648. DOI:10.1073/pnas.67.4.1643. PMC 283405. PMID 5275366.

Milton K (2003). “Micronutrient intakes of wild primates: are humans different?” (PDF). Comp Biochem Physiol a Mol Integr Physiol 136 (1): 47–59. DOI:10.1016/S1095-6433(03)00084-9. PMID 14527629.

Pauling, Linus (1986). How to Live Longer and Feel Better. W. H. Freeman and Company. ISBN 0-380-70289-4. OCLC 15690499 154663991 15690499.

“Dietary Supplement Health and Education Act of 1994”.

Richards E (November 1988). “The Politics of Therapeutic Evaluation: The Vitamin C and Cancer Controversy”. Social Studies of Science 18 (4): 653–701. DOI:10.1177/030631288018004004. JSTOR 284966.

Hickey S, Roberts H (September 2005). “Misleading information on the properties of vitamin C”. PLoS Med. 2 (9): e307; author reply e309. DOI:10.1371/journal.pmed.0020307. PMC 1236801.